A response by Nguyễn Thanh Tâm

to Speaking Nearby: A workshop with Linh Hà, Thu Uyên, & George Clark

On a speaking to expand archives

Interlocuting: What Are Archives For?

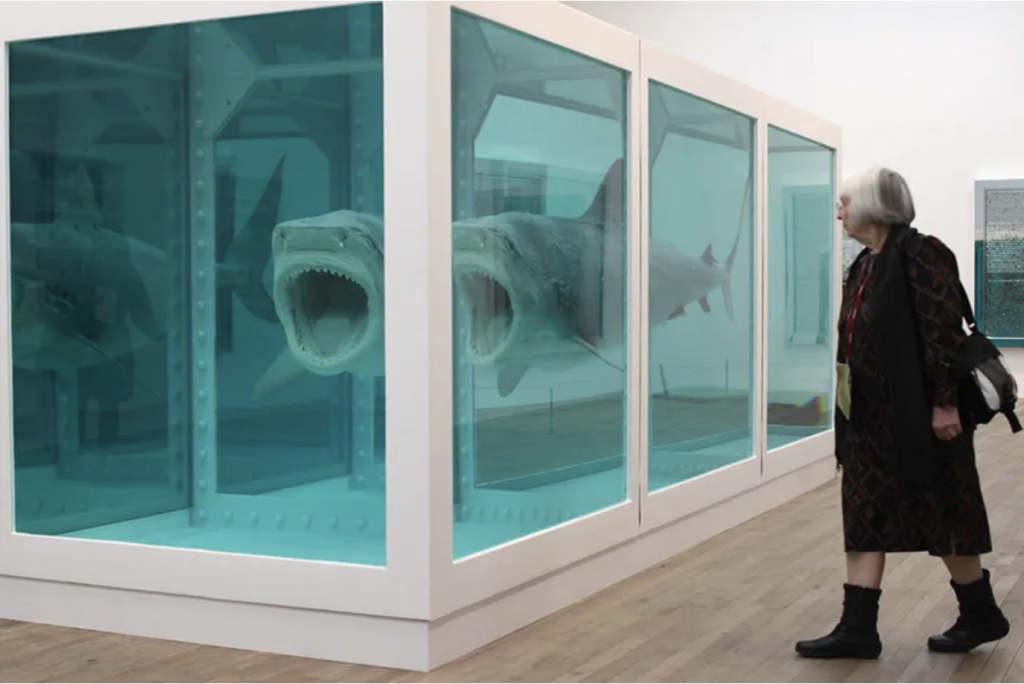

Spatial restoration, temporal recovery of the displaced, came into play through practices centering the uses of historically charged, event-specific found objects, texts mostly under the format of installations. Such works emerge either as a defamiliaring counterattack of the past, a temporal restoration appraising blind spots going unnoticed or a recollation to reiterate its engraved magnitude. Through such a form of tangibility, these works are considered to be bettering the transmissions of history.

If practices with found objects, circulating around a sense of tangibility, strongly underline the duty of collating one event, the archives in Speaking Nearby instead of being stored in tangible form, probing into the realms of fluidity and intangibility, underline self-interrogations of the subject towards its own memories, either collective or personal. The archives embroidered in “Speaking Nearby” transcend known notions of sentient objects to be reincarnated into invisible arks in bodies that when gushing out on palms look like immoral ridges. Here, in Speaking Nearby, the unbridled weigh of having to carry along the never-unpacked memories, archives nourish confessions, yet orally, which births a fragile, perishable archival medium as another way of saying for another one to look at oneself fully, thoroughly is performing autopsy on the inner, demonstrating the disclosement of one’s clandestine wholeness through archives. Here, the stark contrasts in the essence of archives emerge. Archives As Holders of Memories, But Now Are Reforged into Ephemerality. Then I must come to ask: If archives are materialized into such a form of fragility, what is the point of archiving? For the medium chosen for archiving in itself is transient, fleeting and of perishability. Perhaps, archives are not always for archiving. Through Speaking Nearby, we see how the archives interplayed are not for collation, rather, for self-interrogative soliloquies.

“I do not intend to speak about. Just speak nearby”- Trinh T. Minh Ha

Here I begin to wonder, if the archives put into life are non-linear, personally-moulded, should those archives be named archives by all means? “ I do not intend to speak about. Just speak nearby”– Trinh T. Minh Ha. For one, to venture askew around a thing vocally is already an act of destabilizing the nature of the thing. A speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it. – Trinh T. Minh-ha, Visual Anthropology Review, Spring 1992. To speak nearby not directly is to delinearise the way to speak of the thing, to speak of it entropically as to disrupt itself from being unveiled in a flagrant manner and keeping to itself a sense of mystified, past-lurking lugubrity. This way of ambiguous speaking shifts the speaking object to a new nature, a personally-depent nature. With this, the thing spoken nearby is no longer the thing in-it-self, rather, it is subject to transmutations under the force of personalization.

The thing becomes what the executor believes the thing to be; henceforth, festered in the oasis of subjectivity. For that, I apprehend this as not the thing to be in archival, for subjective outlooks on the thing to be in archive ought to be stripped of, in lieu of shaping it. In other words, it means you cannot call the archive of the “personally-transmuted, personally changed” thing archive, if the thing is not depersonalized for outsiders to look into its archive as a blank canvas without any forced-into contemplations. Henceforth, this entwines what I previously wrote: “Perhaps archives are not always for archiving”, and in this, so-called archives hybridize and syncretize memories for the executor to stare unflinchingly into what they themselves have chosen to leave into the marsh of oblivion.

Swaying beyond the utopian illusioned nature of archiving

The births of artworks are not synonymous with the fact that the future will wear on itself the history left of the piece as transmissions of works are invariably wrought with drudgeries. One time, when I was talking to artist Lê Vũ, he mentioned how he, himself, did not know which territories had the documentations of his works drift forwards, dawning on me the perishability of the medium used for archiving. In this modern age, we are often coaxed into believing digital archives are now offered insurance with a life of permanence, partly of what is called digital footprint. But to believe in digital footprint is also to believe in what lies beneath the impact of digital clutter. Time wanes, and one day, much-needed archives, if uncared, go into discarding, so be the advent of the perishable texture of history. Or be the perishability of the artwork? It bears a new mind-invading consciousness that, to a certain extent, the medium in which a piece is archived, dictates the piece’s perceived importance.

Indisputably, archiving is for artworks that have reaped the stage of completion, or to quote Hal Foster, “archival work that centers the project of documentation, and that is where those things are, at least deliberately, done”. But here I would interrogate the phrase “deliberately done” as a stop-inhabiting state of the artworks, coupled to a question that stands erect: For an artwork to live is For itself to be Forever Entwined with [its] Other Preceding Lives? Artworks are permutations; they give lives to permutable variables which demonstrates the artworks’ preposition to outwardly, innerly collide with lives. If artworks are of such permutability, how can we ensure archives of those not to be static, not to be in a fixed posture? Or how can we ensure an artwork is a complete artwork, especially with the constructing dimensional horizons of the work’s contemplations? Or can we think of the nature of archives to be negating, suspending, stifling new lives? Artworks transcribe as a form of promulgating continuities, yet, its limited scope in defining “the state of completion” brings upon a restrictive character of archiving that needs to be reassessed as a perpetuity of discontinuities.

Tracing whose arts are we archiving

A work of historical enormity, is indeed, laden with dubious authenticity and authority. Especially with pieces interweaving found objects, the identity of the author becomes entwined in a blurry, unknown existence. To question the authority of the evaporative author, we trace back the etymology of “author”. From Proto-Italic, “author” etymologically derives from augeō (“to increase, originate”) . If an artist incorporates found objects as a focal lever of their piece, by what extent can the artist proclaim their ownership of the work, as event-specific found objects, in essence, are de-interiorized and de-owned? If every notion of relevance is birthed to be of ambiguity, how do we determine the heralding seeds of the work? Into the abyss of archiving, how do we manifest the type of work we are putting into archives? Assuming archiving practices with found objects, are we archiving the historic events with sentient objects that are event-associated, or are we archiving transcriptions of historically loaded objects by artists? And, if archives are of such unfixed nature, of such mobility, and flexibility, how can we come to the conclusion of what we are archiving? Archiving itself is a double-edged sword as it fogs the rooted ownerships of the work, while bringing about a restrictive definition upon the “conclusion of works”.

References:

- “Author Etymology.” Etymologeek. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://etymologeek.com/eng/author.

- Foster, Hal. “An Archive Impulse.” Monoskop. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://monoskop.org/images/6/6b/Foster_Hal_2004_An_Archival_Impulse.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0flVwtXego8xIp8hhv-pG9hGQ4QwC-KAa-UBKzHYM-ZpZWaGttiLftQko.

- Foucault, Michel. “The Archaeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language.” Accessed June 23, 2022. https://faculty.uml.edu/sgallagher/Foucault_Michel_Archaeology_of_Knowledge.pdf.

- T. Lewis, Charlton. “A Latin Dictionary, Augĕo.” Perseus Digital Library. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=augeo.

VN

VN